On non-declining mammal species number and busting another myth

While there have been a lot of changes in European zoo collections, the overall number of mammal species kept was not one of them. In 2000 there were 637-647 species and in 2023 640-644 species, which if you take the average for each year would mean 642 species kept both in 2000 and 2023. So even when taking the uncertainty into account there has been basically no change. Zootierliste will of course not have been 100% accurate, but it is the best available and I don’t see much reason to not believe that the number of mammal species kept in Europe has been stable compared to the start of the century. Data quality for the most species rich zoos is reliable for the start of the century and even if 10 species were missed (though apart from a few small rodents, I cannot think of any likely misses), that would be a fraction of the total. A hypothetical decrease of 10 species to the 642 now would be quite meaningless.

@Rhino00 Spinifex hopping mice are one species that could have still been present in low numbers in 2000, though it is more likely they had already disappeared before

Zoochatters did however overwhelmingly think that the number of mammal species had decreased. 74% of the people who filled in the questionnaire thought so and only 2 people (5%) predicted no change in the numbers, while 21% thought the number of mammal species kept had increased. The median expected change was a 13% decrease, which would have meant we would have had a net loss of some 83 mammal species this century, given we started off with ±642. Thankfully that did not happen. While there has been no change in the number of species held, most people who filled in the survey assumed that there would be more mammal species in Europe than there are in reality. The median expectation for 2000 was 800 and for 2023 was 723. So even with the expected decrease there was still an expectation of some 80 more mammal species in Europe currently compared to reality.

I think the most important reason for the overestimation is that it is genuinely hard to estimate these numbers, given that a lot of the diversity is hidden in rodents of which some zoos seem to have an endless amount. When making a list of captive mammals I had seen some years ago, I was also surprised how low my total was. Another factor, which was already mentioned by others is that Zootierliste also lists a plethora of subspecies, which further complicates estimating how many species are kept.

@Therabu Barbary lion are one of the many, sometimes questionable, subspecies listed in Zootierliste, obscuring the actual number of species

As to the why people expected a decrease where there is none, I think there are 4 main reasons, 3 of which will be discussed in detail in this post. The first is that it is a favourite pastime of many Zoochatters to bemoan the loss of animal species X from a zoo/country/continent. Such negative stories often seem to have a bigger impact than the positive ones, as it fits into the general narrative of the site. This creates a sort of echo chamber where every loss is a self-fulfilling prophecy of zoos in general allegedly not caring anymore about rare mammals. Gains are still applauded but just seen as a way to somewhat decrease the overall loss. Many species that are lost also have been kept for just a short period of time, so don’t really count on any longer time span. What also happens is that we already calculate for future losses, there are some 30 species which we know will disappear, even though it might take many years in some instances. But these dead ends are a normal thing and 23 years ago there was a comparable number of dead ends as now. Most of those have indeed disappeared, though some have left that category because of additional imports. Species disappearing has always been a common part of the European zoo landscape, but until now these losses were perfectly compensated with new species appearing in their place. Whether this will likely hold in the future will be covered the final mammal post.

@Jogy Eastern gorilla have been a dead end throughout the century, but could remain in Europe for another 20 years

Another part of the story seems to be how easy we forget that some species are relatively new. 24 years ago there were no black-and-rufous sengi, common cusimanse, greater guinea pig, Luzon giant cloud rats or Visayan warty pig in Europe. So while the gains from a few years back are taken for granted, the losses are bemoaned. The hard truth is that losses are just unavoidable in a world where the majority of mammal species is represented only by a few holders and a limited number of individuals. But that is also offset by gains, either from the private sector or overseas. It doesn’t do to focus only on one side of the equation.

@HOMIN96 While only around for 20 years, it feels like bush hyrax have been in Europe forever

Not only is there a common belief that there has been a decrease in mammals, it is also often assumed that the average zoo holds less mammal species compared to 2000. It makes sense to think that if individual zoos hold less species than before, there are also less species than before overall and if not that there are many more rarities now compared to 2000. This also seems to be a wrong assumption. I compared the listings from the International Zoo Yearbooks from 2003 (species data from 1998) with those from 2021 for some 220 European zoos. There actually seems to have been a slight net increase of mammal holdings on the continent in the past 25 years from 13.351 to 13.723 (+2.6%). This estimate is a conservative one as many zoos that are currently expanding at a high pace were tiny in 2000 and weren’t listed in the IZY back then and it is impossible to assess how many mammal species they did have at the time. So for zoos like Noah’s Ark Zoo Farm, Parc Animalier d’Auvergne or Parc Animalier de Sainte Croix, which each have sizable mammal collections now it is not possible to measure exactly how large their increase was. Another reason why the estimate is conservative is because some zoos have numbers listed for 1998, but not 2021. In those cases I have taken a quick Zootierliste search for all mammal taxa as a replacement. While this number includes possible doubling of subspecies, that is outweighed by ignoring domestics, which do seem to be included in the IZY numbers. Data in the IZY are of-course also not 100% accurate, I have the feeling certain zoos give higher numbers than they actually have/had, but that is as much the case for the 1998 as the 2021 data, so should overall not have an impact at the aggregated level.

@Gavial The growth of many French zoos has meant that for carnivores, primates and ungulates holding capacity has increased overall in Europe, with exhibits such as this takin valley in the Auvergne

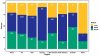

The main reason for this difference between data and perception is probably caused by which zoos have actually had a net loss in species, compared to the zoos that gained species. Overall 91 zoos in the survey had a decrease in mammal species held, compared to 120 with gains. But looking at the ones which have lost species, the ones with the biggest losses are also some of the most known. With Zoo Berlin, Tierpark Berlin, Antwerp, Marwell and Blijdorp as top-5 and other big names such as Artis Amsterdam, London, Wilhelma, Paris Zoo des Vincennes, Leipzig, Lisbon and Munich in the top-25 it is no surprise people think there has been a serious loss. The top-25 of zoos that have gained species is much more varied. It contains the nouveau riche like Pairi Daiza, Sosto and Beauval, but also more under the radar zoos like Beale, Osnabrueck, Opole and Monde Sauvage. But responsible for about half of the overall net gain is Zoo Plzen. While Zoo Plzen is now known as a rarity hunter Valhalla, that only started around the turn of the century, back in 1998 Zoo Plzen had only 48 mammal species. Currently it is the most mammal species rich zoo of them all. While overall the number of mammal holdings has slightly increased, the number of mammals at the most species rich zoos has decreased. While both Berlins had over 200 mammal species each in 1998, no zoo topped 170 in 2021. The number of zoos with more than 100 mammal species has also decreased from 19 to 11 this century. But the median zoo in 1998 held 47 species, compared to 51 species now. So big losses at the top are compensated by smaller gains across the board. Looking at a country level, e.g. Czechia and France have seen a large net gain, whereas Germany has seen a sizable net loss, whereas the United Kingdom is relatively stable. In the Netherlands losses in the 4 big zoos are compensated by the appearance of new zoos (Overloon & Gaiazoo) and gains in other zoos.

@Green_mamba The nouveau riche like Pairi Daiza and many smaller zoos have compensated for species richness losses in the city zoos of old

In the next post we will explore which families & orders have made the largest gains and losses. Given some of the most notable losses have occurred in the most popular orders, this is probably another reason why many people expected a decrease in the number of mammal species held. But that is a story for another time.