Persephone

Well-Known Member

People who follow my travel threads are probably sick and tired of hearing me complain about signage. And I can’t help it! I’m a writer. I wanted to go into science communication once upon a time. I think there are stories behind most zoo animals the vast majority of the public will never know.

But I really can’t fault zoos for often being galleries of pretty animals in pens or landscapes with maybe a sign or two and a decorative feature if they’re lucky. This is what they were designed to be. Places to take a walk and see some pretty things. Zoological gardens. A garden with animals instead of plants.

I want to take the concept to its opposite extreme. Make a pitch for zoological museum exhibits. These exhibits are designed around public education first and foremost with the animals there to tie into the theme of the exhibit and the points being made by signage, artifacts, and displays.

Some notes up front that will apply to most or all of the posts to come:

1) I am not a zookeeper. I have just been to 75+ zoos and aquariums. I have read a fair few care manuals but I won’t get all details right. If some exhibit sizes or features need adjusted let me know.

2) These exhibits will range in size from rather small to very large. I will make notes on modifications to each gallery smaller zoos or museums interested in a living collection could make.

3) Please forgive my renderings my best drafting tool is MS Paint.

4) Exhibit areas will mostly be given in square feet. You can divide by ten to get a rough equivalent in square meters.

5) These exhibits are primarily designed for my home, the northern United States. Animals used will be those reasonably available or importable in those regions. Indoor / outdoor housing decisions are made based on this. You can imagine the alterations to the collection or design that would occur if this was built in another region.

6) Species not found in the AZA but abundant in Europe are fair game, although alternatives will be noted for facilities that don’t want to bother with imports.

Let’s get into the first Proof of Concept.

Furs, Fabrics, and Feathers

This is primarily an exhibit about how we have clothed ourselves through history and the ecological and ethical problems with clothing eight billion people now. The exhibit is also about the animals we use to make clothing and those that have been impacted by our need for furs, fabrics, and feathers. The collection also doubles as a North American exhibit complex featuring exhibits themed to the Northeastern United States, Southwest, Pacific Coast, Mountain West, and Everglades alongside three Eurasian exhibits and two South American species.

Basically, this exhibit is for zoos that want a North America / barnyard exhibit with a twist to stand out or for a rural or city park museum that wants to build a small zoo in the adjacent land. As a result I built it to loop back to a single building. This could also just be a trail for a normal zoo.

Gallery 1: Life On The Savanna

I think the logical place to begin a discussion on the history of clothing is by asking why we have clothes at all. After all, (most) other animals don’t wear them. So, why did we evolve without our own fur and why did we feel the need to make some down the line?

Let’s start with the lack of fur. The leading hypothesis now is that humans lost their fur as they adapted for life on the equatorial savannah. The first part of the exhibit would focus on humans’ other adaptations for heat, like sweating and metabolic shifts.

The exhibit then pivots to discussing how the early humans would have survived on the plains of Africa, including use of persistence hunting. This would discuss humans long legs and unmatched ability for long distance running. We’re well adapted for it. One exhibit could have a treadmill under hot, bright lights and encourage people to see how they run under it. Now imagine doing it in a fur coat.

The rest highly the lives of the San peoples, a primarily hunter-gatherer societiy that live in the context in which humans first evolved. It will have a mock-up of a San dwelling, graphics of the bow and arrows used, a replica rock painting, and broken ostrich eggs (behind glass) which the San use to store and transport water.

There will also be a cluster of exhibits on what happened to the San when Europeans arrived which might need to have a warning for children. There were literally government permits to hunt them until the 1930s. By mid-century most had been forcibly converted to agricultural life.

Of course, some humans left the savanna and entered much colder climes. Humans have some adaptations to the cold, which will be discussed on a graphic, but not enough to survive a temperate winter while naked. This brings us to the two animal exhibits of the first gallery.

By far the larger of the two is a primate exhibit for Japanese macaques. This will be very large for the species at roughly 15,000 square feet to allow for a large troop. I find the social primates much more interesting in groups. The exhibit is primarily naturalistic with climbing features being either rock piles (with caves to get out of direct sunlight or rain) and large real or fake trees. Barren fake trees work better in an exhibit highlighting the primate’s adaptation to cold weather than they do for tropical exhibits. There will also be a water feature that can be heated or cooled depending on the weather. The one exception to the naturalistic emphasis will be tire swings and nets / climbing ropes made with recycled material, emphasized by signage. The rest of the signage can highlight how the world’s other temperate primate evolved to deal with it, including their thick fur.

The other exhibit is a pair of long ~300 gallon aquarium for the giant hermit crab (Petrochirus diogenes) and queen conch (Aliger gigas). Hermit crabs are one of the other animals to wear something like clothing. There can also be a graphic depicting the fad where orca pods in the Pacific Northwest briefly wore salmon as hats. Humans do not have a monopoly on fashion trends.

Potential Alterations:

Japanese macaques are fairly accessible for even small AZA zoos. The exhibit could be smaller for exhibits with limited space. Museums without the space or inclination to care for dozens of mid-sized primates in a large, open area could opt for a smaller exhibit with colobus monkeys or lemurs to show another African primate. This would require indoor viewing if the animals are to be regularly seen in the winter.

Theoretically the exhibit is also large enough for bonobos and they aren’t thematically inappropriate with the emphasis on human evolution in the gallery, but I don’t really want to go in that direction.

Gallery 2: Fur

The logical first solution for not having fur in climates that require it was to simply take it from something else. The start of this gallery covers the ancient history of fur. Obviously, no Paleolithic clothing remains. Instead we just have tools such as hide scrapers, blades, and sewing needles. Real or replica artifacts of these tools and the sort of clothing they could have made start the display. This display could also have models of extinct Paleolithic animals that mankind could have hunted for fur.

The gallery then moves on to more modern fur with a display on the clothing of the indigenous people of the Andes and the domestication of the chinchilla. A pair of doors lead into a dark tunnel. Inside is a reverse-lit exhibit for long-tailed chinchillas. The exhibit is very large for the species at roughly 1,500 square feet, allowing for a larger group of the social species. The exhibit contains a great deal of rockwork to allow for hiding spaces and verticality with a few exercise wheels thrown in. Electronic in the dark area focuses on the behavior of the species and plight of wild chinchilla. It’s fairly minimal compared to the rest of the complex, though.

The gallery then leaves the main building into a mock fur trading post from the height of French colonialism in the New World. Inside the various small structures, both native wigwams and colonial cabins, are exhibits on the fur trade of the era with signage and artifacts/props describing the sort of clothing made from the furs, the Beaver Wars, and the life of both the traders and the native people of the region. There are four exhibits in this part of the gallery. To the right is a 5,000 square foot exhibit that’s primarily a pond with a few grassy areas along the edge. This if for North American beavers. The lodge has a small window in it viewable from inside a small mock cabin.

Ahead is a 3,000 square foot raccoon enclosure. It is fairly swampy with signage emphasizing raccoon’s habits of hunting along the water’s edge and washing their food. Real or fake trees provide for climbing spaces. A fake hollowed log or a wooden crate provides space to hide.

The path then turns to the right and enters a bridge over the beaver pond. On the other side of the bridge is a 2,500 square foot exhibit for American mink. The exhibit has a grassy component, a few hiding places, and a fairly large swimming area. It’s probably a good idea to have some loose netting over the exhibit to keep owls and other predators out.

The signage on the bridge is split by side. One half describes beaver’s role in the ecosystem and the problems caused by their absence and the success of their reintroduction. The other explains what a mink is, how they are similar and different to otters, and why their fur is in such high demand. Ideally there should also be a screen showing a live video feed of the mink’s behind the scenes area and a life-size metal sculpture because guests probably aren’t going to actually see the nocturnal mustelids. Who knows, though? Maybe they’ll get lucky.

The area at the end of the bridge contains a large (~17,500 square foot) exhibit for red and grey foxes. It’s mostly a grassy field with some small hills and a few large trees for shade, variety, and gray fox habitat. The foxes can have various toys or enrichment items like hammocks, small playsets with slides and observation posts, and agility courses. This is where the gallery starts to transition away from the colonial era and into the modern day. The signage should emphasize the many food sources and behavioral adaptations of the red fox that have let them spread across the northern hemisphere. A graphic on another sign can depict the different color morphs of the species.

A glass case will have a few examples of fur in modern fashion with photos around the articles having other examples.

Listen, if you know anything about fur farming the ending of this section should not surprise you. There will be another warning about potential sensitive images and themes alongside examples of the kind of cages captive mink and foxes are stored in alongside written descriptions of the kind of injuries animals routinely suffer. The exhibits in this section were deliberately very large to emphasize the gap between them and the cages at the end.

Alternatives:

These five species are pretty easy to obtain. Admittedly, minks aren’t common in zoos but they’re abundant enough in captivity / as fur farm rescues that it could be made to work. I didn’t add North American river otters here as I wanted the minks to stand out more. Skunks could probably make their way into the raccoon exhibit without issue. The grey fox might also need to be moved there or removed from the collection, depending on the temperament of the foxes. I have seen the fox mix work in larger exhibits, though. Zoos and museums limited on space can shrink the exhibit sizes a fair bit but should still be mindful of the necessary contrast. This is supposed to look like a little slice of natural habitat against a tiny cage, not a tiny cage against a bigger one.

Gallery 3: Leather

Okay, so modern industrial fur farming has its problems. Let’s turn to the skin trade.

The gallery begins outside leading directly out of the end of the fur gallery. There are glass cases, props, and signage discussing the history of leather, from ancient armor through the 1700s. These include displays of the old tanning process in all its noxious glory, complete with some of the plants used and a display on the cleaning process. A sensitizer can let out a small puff of scent attempting to imitate an old tannery.

This leads into a covered porch area looking out on a large (60,000 square foot) field. On the back side of the porch are displays on different leather products used by cowboys and other inhabitants of the American frontier. In the field are Texas longhorn cattle and American quarter-horses. These are both domestics, but I think the horns of the cattle make them interesting enough to headline a gallery. The horses and cattle will need separate barns to allow for the proper dietary supplements to be given.

A set of doors on the side of the porch goes into a “modern leather” gallery. This can begin with modern products such as motorcycle jackets and various hair metal costumes.

It also includes an animal exhibit that’s small for this complex at 500 square feet but still pretty big for its inhabitant, black-and-white tegu. They’re hunted for leather in their native range but their population is stable for the moment. I think tegu and non-Komodo monitor lizards never get the habitats they deserve for their size. There should be several basking places and a pool for bathing or swimming.

Listen, obviously there’s animal cruelty in the leather industry but I just used that angle for the fur trade. I also don’t think that American cattle farming would actually improve much if we just stopped using leather. Instead, I want to focus on pollution.

Modern leather tanning is done with chromium. It’s nasty stuff. And the tanning industry has largely been offshored to South and Southeast Asia where environmental regulations are so lax tanneries can dump thousands of tons of chromium waste a day… in one city. The exhibit should also include an air scrubber and other equipment for environmental and personnel protection that would be required for working with chromium in the United States or Europe, and then the actual equipment used in Asia. Signage can discuss the health and environmental impacts on the communities around modern tanneries in the U.S. and abroad.

Alternatives:

You can totally just use dwarf zebu and Shetland ponies and shrink the exhibit to a tenth of its current size. I just think Texas Longhorn are more interesting and thematically appropriate. Another large cattle breed like Ankole-Watusi or Highland cattle could be used if aesthetics are prioritized.

Gallery 4: Synthetics

Leather sucks. Fur sucks. Got it loud and clear. But isn’t their synthetic leather and fur?

Yes! Let’s talk about it.

Most of that stuff is made from plastic. Plastic is made from oil. After a room discussing this, the exhibit moves into an indoor or outdoor viewing space (take your pick) for the next two species.

This display is themed to the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez oil spill off the coast of Alaska. Graphics should have charts on the number and kinds of animals affected and why. Specifically, it should mention how animals like otters and seabirds tendency to groom themselves just led to them ingesting oil and dying.

There are two main exhibits in this wing. In the Midwest they could be indoors or outdoors, depending on preference. Each exhibit is 10,000 - 12,000 square feet and should have viewing sections above and below the water, potentially stacked on top of each other with ramps allowing access between them. The first exhibits houses sea otters. The exhibit is split between land and water sections like the excellent exhibit at the Minnesota Zoo. The water should be at least 15 feet deep to allow for diving. Signage can discuss any role the zoo plays in caring for orphaned otters, or at least explain where the otters came from. Otters generally have fascinating behaviors that can allow for a lot of species-specific signage. Some of the signage can also emphasize the sea otter’s historic decline due in part to the fur trade.

The second exhibit is for seabirds (horned puffin, tufted puffin, common murre). It should contain large cliffs for nesting in addition to a sizable water feature for diving. Signage can emphasize the problems seabirds have been having in warming oceans, such as “the blob,” a heat wave that killed millions of common murre in the 2010s. In addition to oil spills, fossil fuels also threaten cold weather species indirectly.

The path then (re)enters into a different wing of the same building that contains the indoor leather exhibits. This one has dark walls and is bathed in constantly shifting blue light. It focuses primarily on oceanic plastic pollution. You could fill a whole museum gallery with this theme alone. Displays can include actual objects retrieved from the ocean, the reason microplastics form in the ocean and how they could cause problems through bio accumulation, ghost nets and lines, and finally bags. It’s kind of well known that a lot of marine mammals accidentally eat plastic. This display intends to display why. On one side is an admittedly large (perhaps 6’ by 15’) display of moon jellies. Color changing lights are optional but are always fun. Beside it is another tank with similar dimensions and in the same style with plastic bags and other objects. The walls beside the tanks can have life-sized paintings of leatherback sea turtles and mola molas, two oceanic giants that feed primarily on jellies.

Alternative:

Sea otters are notoriously expensive due to their need for high-quality seafood. This is only realistic for larger zoos. For everything else, The Exxon Valdez display can be replaced with an exhibit on Deepwater Horizon containing species like nurse shark, French grunts, southern stingrays, green morays, a sea turtle, and scrawled filefish in a ~50,000 gallon tank themed around the base of an oil rig. I’ve seen similar exhibits at Fort Wayne Zoo, Greensboro Science Center, and Gladys Porter Zoo. I think this is fair. For zoos and museums that don’t want to go that far a tank with green morays and a stingray touch tank is about as bare-bones as you can get here but does get the point across.

Also the seabird / otter exhibits could probably be cut in half but they’re both fairly energetic species. Sea otters are pretty big for a mustelid and seabirds are really gregarious.

Gallery 5: Wool

What if there was fur but you didn’t have to kill anything to get it? Ah, now we’re closer to a good alternative. Not all the way there but definitely closer.

The gallery stays in the indoor museum for a bit to display various wool clothing (real and replica) made throughout history, as well as distinguishing wool from fur.

The gallery exits into a small strip of path beside a much larger (~20,000 square foot) walkthrough area. Only about half of that is actually accessible to guests, though. This enclosure contains goats, sheep, and alpacas. Different breeds of the caprids can be exhibited to display the different properties of their wool or the difference between a wool and meat sheep. Along the side of the exhibit are barnyard stalls or other fenced off displays with various equipment historically and currently used in harvesting wool. The caprids should have a large climbing structure, ideally well off the guest path running through the walkthrough. The back half of the exhibit is fenced off from guests. If the alpacas really don’t like being around people they can be left back there behind gates too short for them to get through but tall enough for the goats and sheep.

The path loops back to the entry and a hand washing station. Guests enter the next structure through a facade resembling a large yurt. The interior has displays on pastoralism in Mongolia, including the damage the combination of the relaxation of herd sizes and the import of harder-hooves goats for the cashmere trade have done to the country’s grasslands. The yurt exits into the interior of a room themed around the interior of a log cabin. Around it are various signs from different eras in American history offering bounties for wolves and then campaigning for or against their reintroduction. Signage will discuss the politics of wolves in the West (and Southeast) and the gap between rural herders and urbanites on the matter. Graphics, models, or taxidermy of bighorn sheep will point out that much of wolves former prey have been removed from their old habitat and replaced with pastures for domestic sheep. It shouldn’t be too surprising that predators turn towards the new sheep for food.

Outside the cabin is a spacious (~60,000 square foot) exhibit for Mexican gray wolves. The exhibit should be split between open fields and forested areas with rocks and bushes for cover. A large central hill or rock pile can let the wolves look out over their habitat. Brookfield’s wolf exhibit is already near-perfect and I see no need to break the mold it set.

Alternatives:

Realistically, the sheep area can be a lot smaller. It’s mostly that big to allow for the path to loop back around after the oil spill exhibit. Zoos that went with the aquarium option instead can have a smaller habitat with few repercussions. Wolves can also be cut or replaced with cougars for space-limited zoos. Cutting wolves and reducing the size of the cattle exhibit can to cut down the complex’s size by a third.

Gallery 6: Cotton

For better or worse, cotton is the dominant textile in use today. This gallery explores its past, present, and future.

The initial room should contain a view into a small greenhouse containing live cotton plants. Signage should include a mural depicting cotton’s history from antiquity to the present. This does involve one very dark period, American slavery, that is otherwise glossed over in this exhibit because Jesus Christ there’s already been genocide, animal abuse, and climate change maybe we don’t need to get into the darkest chapter of American history. It should at least be referenced in any exhibit on the history of cotton, though. The room should include displays of different cotton garments throughout history and the technologies that have facilitated its rise.

The entry to the next room contains an archway with the words “cotton is thirsty for water” written on top. The next room has two aquariums.

The first depicts the Aral Sea c. 1920. It should be about 30,000 gallons and depict a dockside community through a mural in the background and a pier jutting out into the water. This tank can contain lake sturgeon, northern pike, brown trout, ide, common carp, Wel’s catfish, and zander. Only the pike, trout, carp, and sturgeon are currently found in American collections. The exhibit could be shrunk in half if there are no Wel’s catfish.

Signage should emphasize the ecosystem of the Aral Sea that was, but can be a bit sparse. It should at least emphasize its size relative to whatever the local bodies of water are. That’s the American Great Lakes in my neck of the woods.

Between the two main aquariums is a smaller one with zebra mussels and ruffe with signage reminding visitors that invasive species are always* native to somewhere and they’re perfectly fine in that environment.

The second main aquarium is in a cutaway the same size as the last one, but now the sides are a muddy brown and almost all the water is gone. The pier has rotted and fallen apart and a boat sits on dry land at the bottom of the space. There’s only a relatively shallow puddle of water home to European flounder, but they might be hard to see against the muddy substrate. Signage around and after this display revolves around the history of the Aral Sea’s collapse due to cotton irrigation and ill-advised dams and the ecological havoc it wrought, including models of the sturgeon species that went extinct.

There should also be a display mapping the Ogallala Aquifer. A lot of modern cotton production occurs on the southern Great Plains, and as climate change alters weather patterns there’s a serious risk of the aquifer drying up due to excess consumption for cotton irrigation, potentially doing serious harm to the people reliant on it for water.

Gallery 7: Silk

This is the shortest of the galleries. The entry hall has the standard array of items and historic displays, leading up to a row of terrariums for the domestic silkworm. There should be multiple terrariums as otherwise the bottlenecking will get really serious. There can also be an emergence area for silk moths but they can’t actually fly well so it doesn’t need to be very big. Signage needs and crowd control push the exhibit size up more than animal welfare.

The problem with silk is ethical, again. The best silk is made from unbroken cocoons. So the silkworms are boiled alive in them. The reveal can be dramatically framed, with words over an arched doorway reading “The problem with silk is…”

This proceeds into a room where many cocoons are “boiling” in glass containers. These are props being disturbed by bubble effects with some water vapor spraying out the top. Actually heating lots of props 24/7 sounds expensive and dangerous. Beneath the containers the text finished: “…these caterpillars are still alive.” One sign will explain that the cocoons on display aren’t real in case people have ethical concerns.

This is the one and only time that the textile-specific gallery ends by proposing alternatives. Silk can be collected from the shed cocoons of wild silk moths. This is called ahimsa silk. The reason Ghandi was often photographed with a spinning wheel is because he strongly advocated for making clothing out of cotton as it did not involve killing animals. Ideally, this would transition into the cotton gallery. But I had to put that first so the aquariums were closer together and could share infrastructure. If there are any alterations made from the template proposal then silk could probably be moved first. Otherwise there are no alterations for size or cost because the only species on display is a tiny domestic.

Gallery 8: Feathers

The silk gallery exits into a dark room with video themed to a newsreel playing. The doors only open between showings, but I can be bypassed through another door.

The video is actually anachronistic since audiovisual newsreels didn’t exist until decades after the events described, but most people won’t know that.

The video begins by describing a new trend in women’s fashion to put feathers in their hats, especially from the roseate spoonbill. It then pivots to increasing pressure from early conservationists to protect the spoonbill’s breeding habitats and prevent their hunting. It then covers a few policy victories for conservationists in South Florida such as the passing of the Lacey Act, Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and the establishment of the first National Wildlife Refuge on Pelican Island off the coast of Florida.

Another set of doors then opens into a greenhouse aviary with a prominent sign welcoming guests to Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge. The greenhouse is large at roughly 18,000 square feet. Two-thirds are a walkthrough aviary with smaller birds and a reptile. The back third is a separate aviary.

The first aviary is a mix of thick foliage and a mangrove swamp with a grassy clearing and a more open pond for species that prefer those habitats. The first aviary contains roseate spoonbill, white ibis, gopher tortoise, red-winged blackbird, Baltimore oriole, common grackle, northern bobwhite, killdeer, snowy egret, redhead, wood duck, gadwalls, and bufflehead. Signage of the present species is found throughout the exhibit but lists little more than their images and names. Signage describing the conservation history of specific species like roseate spoonbill, snowy egret, wood duck, and gopher tortoise is found where the animals are most likely to be.

The back third is accessible through a set of doors leading into a separate, netted off aviary. The species here are great blue heron, brown pelican, and herring gulls. The environment is more dominated by water with a few wooden posts sticking from the water, a rocky island in the middle, and a sandy beach in the back. Palm trees and a rock formation provide space for the gulls to get off the ground The water depth is shallow enough that the heron can wade through most of it while still being deep enough for pelicans to swim. A few deeper areas are found, especially near the guest’s viewing platform. Each of the three species has signage describing their adaptations to coastal life (legs, pouches, and intellect), as well as an extra sign on the reason Pelican Island was protected in the first place.

On the way out is an enclosed glass box housing Perdido Key Beach Mouse with signage describing the reason for their decline. The exhibit should have plenty of hiding places for the mice since it’s otherwise fairly exposed.

After exiting the aviary there is a set of metallic statues or busts of various figures instrumental to this conservation success story, including Theodore Roosevelt, John Lacey, Marjory Stoneman Douglass, Paul Kroegel, and Guy Bradley. There will also be a mural for the one bird that wasn’t saved in time, the Carolina parakeet.

Next are the last three animal exhibits, all for the American alligator. One is a relatively small (200 square foot) tank for hatchlings. The second is an indoor display for adults that’s about 5,000 square feet. Last is an outdoor courtyard for adults that’s roughly 15,000 square feet. A boardwalk extends out over it to a pavilion overlooking the water. Alligators also declined precipitously, in part due to the desire for their hides, but were able to rebound due to conservation efforts in Florida.

I do want to end the animal displays on a hopeful note, that it is in fact possible to confront serious environmental problems and change course before it’s too late.

Alternatives:

The adult alligators could be removed and the Pelican Island aviary shrunk considerably for zoos limited on space. Perdido Beach Key mice have few holders but I know in the 2010s they were interested in expanding. It just seems like a good way for the zoo to do actual conservation work in a display of mostly native species. The display could be removed entirely or filled with a different smaller species, perhaps a snake, if the mice are unavailable.

Gallery 9: The Path Forwards

The final gallery has no live animals and is also far and away the most important of the complex. Seven of the last eight have been depressing, but the point at the end is that there are solutions to our problems, many of which guests can participate in at home.

There are four prongs here. The first is reducing impact. There are ways to make clothing materials in less ethically dubious ways. Ahimsa silk was mentioned before. Fungus-based and cell-cultured leather are in their infancy but show promise. Technological advances have allowed for bamboo fibers, which are a lot better for the environment than the alternatives as long as we don’t overdo it and bulldoze entire ecosystems to grow bamboo in its place. Flax-derived linen is a good substitute for cotton since it’s less water intensive than cotton. Laws could be passed mandating improved conditions in the fur industry and cracking down on plastics. And consumers can pay attention to where their leather is made.

This brings us to the three R’s of the environmental movement. Recycle is last because it’s supposed to be the least important. Yes, some plastics can be recycled… but they rarely are. Denim can be downcycled.

Reuse is more important. Clothing can be turned into quilts. You can always thrift instead of buying new. Old fur and leather doesn’t require new slaughter. But it’s still less important than the first R.

The bulk of this gallery is about fast fashion and how to properly take care of clothes. The problem isn’t just clothing eight billion people, it’s also making loads of garments that get thrown away after a use or two. Clothing is a necessity, ecologically, legally, and culturally. But you also don’t need to hoard it. This display highlights what clothing is the most durable and, more importantly, how to care for it to increase longevity. Forget information on lions in Kenya, if you want people to do conservation tell them what the washer settings do and what goes with each one. Why some things need hand washed or dry cleaned and what it does to their longevity when you don’t. Sponsor sewing classes in local libraries and community centers. Maybe subsidize a local fabric store. Help people care for the stuff they have so they don’t need to buy as much.

And also use some shame by highlighting why fast fashion in particular is an ecological scourge.

The point of this exhibit is not that all textiles are bad and you should feel bad for using them. It’s that using too much or in the wrong way can do real harm to animals, people, and environments. Be mindful when you shop.

I don’t love closing exhibits on a gift shop but it is helpful here. Stock it full of books on the many subjects touched upon in the exhibit, zoo merch with information on how it was made / sourced, and some basic sewing equipment.

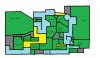

Key to my MSPaint map:

Grey = Staff Area

Blue = Indoor Visitor Space

Yellow = Outdoor Visitor Space

Green = Animal Exhibit.

The full exhibit is about nine acres. That’s very big, but about in line for a continent complex at a major zoo.

But I really can’t fault zoos for often being galleries of pretty animals in pens or landscapes with maybe a sign or two and a decorative feature if they’re lucky. This is what they were designed to be. Places to take a walk and see some pretty things. Zoological gardens. A garden with animals instead of plants.

I want to take the concept to its opposite extreme. Make a pitch for zoological museum exhibits. These exhibits are designed around public education first and foremost with the animals there to tie into the theme of the exhibit and the points being made by signage, artifacts, and displays.

Some notes up front that will apply to most or all of the posts to come:

1) I am not a zookeeper. I have just been to 75+ zoos and aquariums. I have read a fair few care manuals but I won’t get all details right. If some exhibit sizes or features need adjusted let me know.

2) These exhibits will range in size from rather small to very large. I will make notes on modifications to each gallery smaller zoos or museums interested in a living collection could make.

3) Please forgive my renderings my best drafting tool is MS Paint.

4) Exhibit areas will mostly be given in square feet. You can divide by ten to get a rough equivalent in square meters.

5) These exhibits are primarily designed for my home, the northern United States. Animals used will be those reasonably available or importable in those regions. Indoor / outdoor housing decisions are made based on this. You can imagine the alterations to the collection or design that would occur if this was built in another region.

6) Species not found in the AZA but abundant in Europe are fair game, although alternatives will be noted for facilities that don’t want to bother with imports.

Let’s get into the first Proof of Concept.

Furs, Fabrics, and Feathers

This is primarily an exhibit about how we have clothed ourselves through history and the ecological and ethical problems with clothing eight billion people now. The exhibit is also about the animals we use to make clothing and those that have been impacted by our need for furs, fabrics, and feathers. The collection also doubles as a North American exhibit complex featuring exhibits themed to the Northeastern United States, Southwest, Pacific Coast, Mountain West, and Everglades alongside three Eurasian exhibits and two South American species.

Basically, this exhibit is for zoos that want a North America / barnyard exhibit with a twist to stand out or for a rural or city park museum that wants to build a small zoo in the adjacent land. As a result I built it to loop back to a single building. This could also just be a trail for a normal zoo.

Gallery 1: Life On The Savanna

I think the logical place to begin a discussion on the history of clothing is by asking why we have clothes at all. After all, (most) other animals don’t wear them. So, why did we evolve without our own fur and why did we feel the need to make some down the line?

Let’s start with the lack of fur. The leading hypothesis now is that humans lost their fur as they adapted for life on the equatorial savannah. The first part of the exhibit would focus on humans’ other adaptations for heat, like sweating and metabolic shifts.

The exhibit then pivots to discussing how the early humans would have survived on the plains of Africa, including use of persistence hunting. This would discuss humans long legs and unmatched ability for long distance running. We’re well adapted for it. One exhibit could have a treadmill under hot, bright lights and encourage people to see how they run under it. Now imagine doing it in a fur coat.

The rest highly the lives of the San peoples, a primarily hunter-gatherer societiy that live in the context in which humans first evolved. It will have a mock-up of a San dwelling, graphics of the bow and arrows used, a replica rock painting, and broken ostrich eggs (behind glass) which the San use to store and transport water.

There will also be a cluster of exhibits on what happened to the San when Europeans arrived which might need to have a warning for children. There were literally government permits to hunt them until the 1930s. By mid-century most had been forcibly converted to agricultural life.

Of course, some humans left the savanna and entered much colder climes. Humans have some adaptations to the cold, which will be discussed on a graphic, but not enough to survive a temperate winter while naked. This brings us to the two animal exhibits of the first gallery.

By far the larger of the two is a primate exhibit for Japanese macaques. This will be very large for the species at roughly 15,000 square feet to allow for a large troop. I find the social primates much more interesting in groups. The exhibit is primarily naturalistic with climbing features being either rock piles (with caves to get out of direct sunlight or rain) and large real or fake trees. Barren fake trees work better in an exhibit highlighting the primate’s adaptation to cold weather than they do for tropical exhibits. There will also be a water feature that can be heated or cooled depending on the weather. The one exception to the naturalistic emphasis will be tire swings and nets / climbing ropes made with recycled material, emphasized by signage. The rest of the signage can highlight how the world’s other temperate primate evolved to deal with it, including their thick fur.

The other exhibit is a pair of long ~300 gallon aquarium for the giant hermit crab (Petrochirus diogenes) and queen conch (Aliger gigas). Hermit crabs are one of the other animals to wear something like clothing. There can also be a graphic depicting the fad where orca pods in the Pacific Northwest briefly wore salmon as hats. Humans do not have a monopoly on fashion trends.

Potential Alterations:

Japanese macaques are fairly accessible for even small AZA zoos. The exhibit could be smaller for exhibits with limited space. Museums without the space or inclination to care for dozens of mid-sized primates in a large, open area could opt for a smaller exhibit with colobus monkeys or lemurs to show another African primate. This would require indoor viewing if the animals are to be regularly seen in the winter.

Theoretically the exhibit is also large enough for bonobos and they aren’t thematically inappropriate with the emphasis on human evolution in the gallery, but I don’t really want to go in that direction.

Gallery 2: Fur

The logical first solution for not having fur in climates that require it was to simply take it from something else. The start of this gallery covers the ancient history of fur. Obviously, no Paleolithic clothing remains. Instead we just have tools such as hide scrapers, blades, and sewing needles. Real or replica artifacts of these tools and the sort of clothing they could have made start the display. This display could also have models of extinct Paleolithic animals that mankind could have hunted for fur.

The gallery then moves on to more modern fur with a display on the clothing of the indigenous people of the Andes and the domestication of the chinchilla. A pair of doors lead into a dark tunnel. Inside is a reverse-lit exhibit for long-tailed chinchillas. The exhibit is very large for the species at roughly 1,500 square feet, allowing for a larger group of the social species. The exhibit contains a great deal of rockwork to allow for hiding spaces and verticality with a few exercise wheels thrown in. Electronic in the dark area focuses on the behavior of the species and plight of wild chinchilla. It’s fairly minimal compared to the rest of the complex, though.

The gallery then leaves the main building into a mock fur trading post from the height of French colonialism in the New World. Inside the various small structures, both native wigwams and colonial cabins, are exhibits on the fur trade of the era with signage and artifacts/props describing the sort of clothing made from the furs, the Beaver Wars, and the life of both the traders and the native people of the region. There are four exhibits in this part of the gallery. To the right is a 5,000 square foot exhibit that’s primarily a pond with a few grassy areas along the edge. This if for North American beavers. The lodge has a small window in it viewable from inside a small mock cabin.

Ahead is a 3,000 square foot raccoon enclosure. It is fairly swampy with signage emphasizing raccoon’s habits of hunting along the water’s edge and washing their food. Real or fake trees provide for climbing spaces. A fake hollowed log or a wooden crate provides space to hide.

The path then turns to the right and enters a bridge over the beaver pond. On the other side of the bridge is a 2,500 square foot exhibit for American mink. The exhibit has a grassy component, a few hiding places, and a fairly large swimming area. It’s probably a good idea to have some loose netting over the exhibit to keep owls and other predators out.

The signage on the bridge is split by side. One half describes beaver’s role in the ecosystem and the problems caused by their absence and the success of their reintroduction. The other explains what a mink is, how they are similar and different to otters, and why their fur is in such high demand. Ideally there should also be a screen showing a live video feed of the mink’s behind the scenes area and a life-size metal sculpture because guests probably aren’t going to actually see the nocturnal mustelids. Who knows, though? Maybe they’ll get lucky.

The area at the end of the bridge contains a large (~17,500 square foot) exhibit for red and grey foxes. It’s mostly a grassy field with some small hills and a few large trees for shade, variety, and gray fox habitat. The foxes can have various toys or enrichment items like hammocks, small playsets with slides and observation posts, and agility courses. This is where the gallery starts to transition away from the colonial era and into the modern day. The signage should emphasize the many food sources and behavioral adaptations of the red fox that have let them spread across the northern hemisphere. A graphic on another sign can depict the different color morphs of the species.

A glass case will have a few examples of fur in modern fashion with photos around the articles having other examples.

Listen, if you know anything about fur farming the ending of this section should not surprise you. There will be another warning about potential sensitive images and themes alongside examples of the kind of cages captive mink and foxes are stored in alongside written descriptions of the kind of injuries animals routinely suffer. The exhibits in this section were deliberately very large to emphasize the gap between them and the cages at the end.

Alternatives:

These five species are pretty easy to obtain. Admittedly, minks aren’t common in zoos but they’re abundant enough in captivity / as fur farm rescues that it could be made to work. I didn’t add North American river otters here as I wanted the minks to stand out more. Skunks could probably make their way into the raccoon exhibit without issue. The grey fox might also need to be moved there or removed from the collection, depending on the temperament of the foxes. I have seen the fox mix work in larger exhibits, though. Zoos and museums limited on space can shrink the exhibit sizes a fair bit but should still be mindful of the necessary contrast. This is supposed to look like a little slice of natural habitat against a tiny cage, not a tiny cage against a bigger one.

Gallery 3: Leather

Okay, so modern industrial fur farming has its problems. Let’s turn to the skin trade.

The gallery begins outside leading directly out of the end of the fur gallery. There are glass cases, props, and signage discussing the history of leather, from ancient armor through the 1700s. These include displays of the old tanning process in all its noxious glory, complete with some of the plants used and a display on the cleaning process. A sensitizer can let out a small puff of scent attempting to imitate an old tannery.

This leads into a covered porch area looking out on a large (60,000 square foot) field. On the back side of the porch are displays on different leather products used by cowboys and other inhabitants of the American frontier. In the field are Texas longhorn cattle and American quarter-horses. These are both domestics, but I think the horns of the cattle make them interesting enough to headline a gallery. The horses and cattle will need separate barns to allow for the proper dietary supplements to be given.

A set of doors on the side of the porch goes into a “modern leather” gallery. This can begin with modern products such as motorcycle jackets and various hair metal costumes.

It also includes an animal exhibit that’s small for this complex at 500 square feet but still pretty big for its inhabitant, black-and-white tegu. They’re hunted for leather in their native range but their population is stable for the moment. I think tegu and non-Komodo monitor lizards never get the habitats they deserve for their size. There should be several basking places and a pool for bathing or swimming.

Listen, obviously there’s animal cruelty in the leather industry but I just used that angle for the fur trade. I also don’t think that American cattle farming would actually improve much if we just stopped using leather. Instead, I want to focus on pollution.

Modern leather tanning is done with chromium. It’s nasty stuff. And the tanning industry has largely been offshored to South and Southeast Asia where environmental regulations are so lax tanneries can dump thousands of tons of chromium waste a day… in one city. The exhibit should also include an air scrubber and other equipment for environmental and personnel protection that would be required for working with chromium in the United States or Europe, and then the actual equipment used in Asia. Signage can discuss the health and environmental impacts on the communities around modern tanneries in the U.S. and abroad.

Alternatives:

You can totally just use dwarf zebu and Shetland ponies and shrink the exhibit to a tenth of its current size. I just think Texas Longhorn are more interesting and thematically appropriate. Another large cattle breed like Ankole-Watusi or Highland cattle could be used if aesthetics are prioritized.

Gallery 4: Synthetics

Leather sucks. Fur sucks. Got it loud and clear. But isn’t their synthetic leather and fur?

Yes! Let’s talk about it.

Most of that stuff is made from plastic. Plastic is made from oil. After a room discussing this, the exhibit moves into an indoor or outdoor viewing space (take your pick) for the next two species.

This display is themed to the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez oil spill off the coast of Alaska. Graphics should have charts on the number and kinds of animals affected and why. Specifically, it should mention how animals like otters and seabirds tendency to groom themselves just led to them ingesting oil and dying.

There are two main exhibits in this wing. In the Midwest they could be indoors or outdoors, depending on preference. Each exhibit is 10,000 - 12,000 square feet and should have viewing sections above and below the water, potentially stacked on top of each other with ramps allowing access between them. The first exhibits houses sea otters. The exhibit is split between land and water sections like the excellent exhibit at the Minnesota Zoo. The water should be at least 15 feet deep to allow for diving. Signage can discuss any role the zoo plays in caring for orphaned otters, or at least explain where the otters came from. Otters generally have fascinating behaviors that can allow for a lot of species-specific signage. Some of the signage can also emphasize the sea otter’s historic decline due in part to the fur trade.

The second exhibit is for seabirds (horned puffin, tufted puffin, common murre). It should contain large cliffs for nesting in addition to a sizable water feature for diving. Signage can emphasize the problems seabirds have been having in warming oceans, such as “the blob,” a heat wave that killed millions of common murre in the 2010s. In addition to oil spills, fossil fuels also threaten cold weather species indirectly.

The path then (re)enters into a different wing of the same building that contains the indoor leather exhibits. This one has dark walls and is bathed in constantly shifting blue light. It focuses primarily on oceanic plastic pollution. You could fill a whole museum gallery with this theme alone. Displays can include actual objects retrieved from the ocean, the reason microplastics form in the ocean and how they could cause problems through bio accumulation, ghost nets and lines, and finally bags. It’s kind of well known that a lot of marine mammals accidentally eat plastic. This display intends to display why. On one side is an admittedly large (perhaps 6’ by 15’) display of moon jellies. Color changing lights are optional but are always fun. Beside it is another tank with similar dimensions and in the same style with plastic bags and other objects. The walls beside the tanks can have life-sized paintings of leatherback sea turtles and mola molas, two oceanic giants that feed primarily on jellies.

Alternative:

Sea otters are notoriously expensive due to their need for high-quality seafood. This is only realistic for larger zoos. For everything else, The Exxon Valdez display can be replaced with an exhibit on Deepwater Horizon containing species like nurse shark, French grunts, southern stingrays, green morays, a sea turtle, and scrawled filefish in a ~50,000 gallon tank themed around the base of an oil rig. I’ve seen similar exhibits at Fort Wayne Zoo, Greensboro Science Center, and Gladys Porter Zoo. I think this is fair. For zoos and museums that don’t want to go that far a tank with green morays and a stingray touch tank is about as bare-bones as you can get here but does get the point across.

Also the seabird / otter exhibits could probably be cut in half but they’re both fairly energetic species. Sea otters are pretty big for a mustelid and seabirds are really gregarious.

Gallery 5: Wool

What if there was fur but you didn’t have to kill anything to get it? Ah, now we’re closer to a good alternative. Not all the way there but definitely closer.

The gallery stays in the indoor museum for a bit to display various wool clothing (real and replica) made throughout history, as well as distinguishing wool from fur.

The gallery exits into a small strip of path beside a much larger (~20,000 square foot) walkthrough area. Only about half of that is actually accessible to guests, though. This enclosure contains goats, sheep, and alpacas. Different breeds of the caprids can be exhibited to display the different properties of their wool or the difference between a wool and meat sheep. Along the side of the exhibit are barnyard stalls or other fenced off displays with various equipment historically and currently used in harvesting wool. The caprids should have a large climbing structure, ideally well off the guest path running through the walkthrough. The back half of the exhibit is fenced off from guests. If the alpacas really don’t like being around people they can be left back there behind gates too short for them to get through but tall enough for the goats and sheep.

The path loops back to the entry and a hand washing station. Guests enter the next structure through a facade resembling a large yurt. The interior has displays on pastoralism in Mongolia, including the damage the combination of the relaxation of herd sizes and the import of harder-hooves goats for the cashmere trade have done to the country’s grasslands. The yurt exits into the interior of a room themed around the interior of a log cabin. Around it are various signs from different eras in American history offering bounties for wolves and then campaigning for or against their reintroduction. Signage will discuss the politics of wolves in the West (and Southeast) and the gap between rural herders and urbanites on the matter. Graphics, models, or taxidermy of bighorn sheep will point out that much of wolves former prey have been removed from their old habitat and replaced with pastures for domestic sheep. It shouldn’t be too surprising that predators turn towards the new sheep for food.

Outside the cabin is a spacious (~60,000 square foot) exhibit for Mexican gray wolves. The exhibit should be split between open fields and forested areas with rocks and bushes for cover. A large central hill or rock pile can let the wolves look out over their habitat. Brookfield’s wolf exhibit is already near-perfect and I see no need to break the mold it set.

Alternatives:

Realistically, the sheep area can be a lot smaller. It’s mostly that big to allow for the path to loop back around after the oil spill exhibit. Zoos that went with the aquarium option instead can have a smaller habitat with few repercussions. Wolves can also be cut or replaced with cougars for space-limited zoos. Cutting wolves and reducing the size of the cattle exhibit can to cut down the complex’s size by a third.

Gallery 6: Cotton

For better or worse, cotton is the dominant textile in use today. This gallery explores its past, present, and future.

The initial room should contain a view into a small greenhouse containing live cotton plants. Signage should include a mural depicting cotton’s history from antiquity to the present. This does involve one very dark period, American slavery, that is otherwise glossed over in this exhibit because Jesus Christ there’s already been genocide, animal abuse, and climate change maybe we don’t need to get into the darkest chapter of American history. It should at least be referenced in any exhibit on the history of cotton, though. The room should include displays of different cotton garments throughout history and the technologies that have facilitated its rise.

The entry to the next room contains an archway with the words “cotton is thirsty for water” written on top. The next room has two aquariums.

The first depicts the Aral Sea c. 1920. It should be about 30,000 gallons and depict a dockside community through a mural in the background and a pier jutting out into the water. This tank can contain lake sturgeon, northern pike, brown trout, ide, common carp, Wel’s catfish, and zander. Only the pike, trout, carp, and sturgeon are currently found in American collections. The exhibit could be shrunk in half if there are no Wel’s catfish.

Signage should emphasize the ecosystem of the Aral Sea that was, but can be a bit sparse. It should at least emphasize its size relative to whatever the local bodies of water are. That’s the American Great Lakes in my neck of the woods.

Between the two main aquariums is a smaller one with zebra mussels and ruffe with signage reminding visitors that invasive species are always* native to somewhere and they’re perfectly fine in that environment.

The second main aquarium is in a cutaway the same size as the last one, but now the sides are a muddy brown and almost all the water is gone. The pier has rotted and fallen apart and a boat sits on dry land at the bottom of the space. There’s only a relatively shallow puddle of water home to European flounder, but they might be hard to see against the muddy substrate. Signage around and after this display revolves around the history of the Aral Sea’s collapse due to cotton irrigation and ill-advised dams and the ecological havoc it wrought, including models of the sturgeon species that went extinct.

There should also be a display mapping the Ogallala Aquifer. A lot of modern cotton production occurs on the southern Great Plains, and as climate change alters weather patterns there’s a serious risk of the aquifer drying up due to excess consumption for cotton irrigation, potentially doing serious harm to the people reliant on it for water.

Gallery 7: Silk

This is the shortest of the galleries. The entry hall has the standard array of items and historic displays, leading up to a row of terrariums for the domestic silkworm. There should be multiple terrariums as otherwise the bottlenecking will get really serious. There can also be an emergence area for silk moths but they can’t actually fly well so it doesn’t need to be very big. Signage needs and crowd control push the exhibit size up more than animal welfare.

The problem with silk is ethical, again. The best silk is made from unbroken cocoons. So the silkworms are boiled alive in them. The reveal can be dramatically framed, with words over an arched doorway reading “The problem with silk is…”

This proceeds into a room where many cocoons are “boiling” in glass containers. These are props being disturbed by bubble effects with some water vapor spraying out the top. Actually heating lots of props 24/7 sounds expensive and dangerous. Beneath the containers the text finished: “…these caterpillars are still alive.” One sign will explain that the cocoons on display aren’t real in case people have ethical concerns.

This is the one and only time that the textile-specific gallery ends by proposing alternatives. Silk can be collected from the shed cocoons of wild silk moths. This is called ahimsa silk. The reason Ghandi was often photographed with a spinning wheel is because he strongly advocated for making clothing out of cotton as it did not involve killing animals. Ideally, this would transition into the cotton gallery. But I had to put that first so the aquariums were closer together and could share infrastructure. If there are any alterations made from the template proposal then silk could probably be moved first. Otherwise there are no alterations for size or cost because the only species on display is a tiny domestic.

Gallery 8: Feathers

The silk gallery exits into a dark room with video themed to a newsreel playing. The doors only open between showings, but I can be bypassed through another door.

The video is actually anachronistic since audiovisual newsreels didn’t exist until decades after the events described, but most people won’t know that.

The video begins by describing a new trend in women’s fashion to put feathers in their hats, especially from the roseate spoonbill. It then pivots to increasing pressure from early conservationists to protect the spoonbill’s breeding habitats and prevent their hunting. It then covers a few policy victories for conservationists in South Florida such as the passing of the Lacey Act, Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and the establishment of the first National Wildlife Refuge on Pelican Island off the coast of Florida.

Another set of doors then opens into a greenhouse aviary with a prominent sign welcoming guests to Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge. The greenhouse is large at roughly 18,000 square feet. Two-thirds are a walkthrough aviary with smaller birds and a reptile. The back third is a separate aviary.

The first aviary is a mix of thick foliage and a mangrove swamp with a grassy clearing and a more open pond for species that prefer those habitats. The first aviary contains roseate spoonbill, white ibis, gopher tortoise, red-winged blackbird, Baltimore oriole, common grackle, northern bobwhite, killdeer, snowy egret, redhead, wood duck, gadwalls, and bufflehead. Signage of the present species is found throughout the exhibit but lists little more than their images and names. Signage describing the conservation history of specific species like roseate spoonbill, snowy egret, wood duck, and gopher tortoise is found where the animals are most likely to be.

The back third is accessible through a set of doors leading into a separate, netted off aviary. The species here are great blue heron, brown pelican, and herring gulls. The environment is more dominated by water with a few wooden posts sticking from the water, a rocky island in the middle, and a sandy beach in the back. Palm trees and a rock formation provide space for the gulls to get off the ground The water depth is shallow enough that the heron can wade through most of it while still being deep enough for pelicans to swim. A few deeper areas are found, especially near the guest’s viewing platform. Each of the three species has signage describing their adaptations to coastal life (legs, pouches, and intellect), as well as an extra sign on the reason Pelican Island was protected in the first place.

On the way out is an enclosed glass box housing Perdido Key Beach Mouse with signage describing the reason for their decline. The exhibit should have plenty of hiding places for the mice since it’s otherwise fairly exposed.

After exiting the aviary there is a set of metallic statues or busts of various figures instrumental to this conservation success story, including Theodore Roosevelt, John Lacey, Marjory Stoneman Douglass, Paul Kroegel, and Guy Bradley. There will also be a mural for the one bird that wasn’t saved in time, the Carolina parakeet.

Next are the last three animal exhibits, all for the American alligator. One is a relatively small (200 square foot) tank for hatchlings. The second is an indoor display for adults that’s about 5,000 square feet. Last is an outdoor courtyard for adults that’s roughly 15,000 square feet. A boardwalk extends out over it to a pavilion overlooking the water. Alligators also declined precipitously, in part due to the desire for their hides, but were able to rebound due to conservation efforts in Florida.

I do want to end the animal displays on a hopeful note, that it is in fact possible to confront serious environmental problems and change course before it’s too late.

Alternatives:

The adult alligators could be removed and the Pelican Island aviary shrunk considerably for zoos limited on space. Perdido Beach Key mice have few holders but I know in the 2010s they were interested in expanding. It just seems like a good way for the zoo to do actual conservation work in a display of mostly native species. The display could be removed entirely or filled with a different smaller species, perhaps a snake, if the mice are unavailable.

Gallery 9: The Path Forwards

The final gallery has no live animals and is also far and away the most important of the complex. Seven of the last eight have been depressing, but the point at the end is that there are solutions to our problems, many of which guests can participate in at home.

There are four prongs here. The first is reducing impact. There are ways to make clothing materials in less ethically dubious ways. Ahimsa silk was mentioned before. Fungus-based and cell-cultured leather are in their infancy but show promise. Technological advances have allowed for bamboo fibers, which are a lot better for the environment than the alternatives as long as we don’t overdo it and bulldoze entire ecosystems to grow bamboo in its place. Flax-derived linen is a good substitute for cotton since it’s less water intensive than cotton. Laws could be passed mandating improved conditions in the fur industry and cracking down on plastics. And consumers can pay attention to where their leather is made.

This brings us to the three R’s of the environmental movement. Recycle is last because it’s supposed to be the least important. Yes, some plastics can be recycled… but they rarely are. Denim can be downcycled.

Reuse is more important. Clothing can be turned into quilts. You can always thrift instead of buying new. Old fur and leather doesn’t require new slaughter. But it’s still less important than the first R.

The bulk of this gallery is about fast fashion and how to properly take care of clothes. The problem isn’t just clothing eight billion people, it’s also making loads of garments that get thrown away after a use or two. Clothing is a necessity, ecologically, legally, and culturally. But you also don’t need to hoard it. This display highlights what clothing is the most durable and, more importantly, how to care for it to increase longevity. Forget information on lions in Kenya, if you want people to do conservation tell them what the washer settings do and what goes with each one. Why some things need hand washed or dry cleaned and what it does to their longevity when you don’t. Sponsor sewing classes in local libraries and community centers. Maybe subsidize a local fabric store. Help people care for the stuff they have so they don’t need to buy as much.

And also use some shame by highlighting why fast fashion in particular is an ecological scourge.

The point of this exhibit is not that all textiles are bad and you should feel bad for using them. It’s that using too much or in the wrong way can do real harm to animals, people, and environments. Be mindful when you shop.

I don’t love closing exhibits on a gift shop but it is helpful here. Stock it full of books on the many subjects touched upon in the exhibit, zoo merch with information on how it was made / sourced, and some basic sewing equipment.

Key to my MSPaint map:

Grey = Staff Area

Blue = Indoor Visitor Space

Yellow = Outdoor Visitor Space

Green = Animal Exhibit.

The full exhibit is about nine acres. That’s very big, but about in line for a continent complex at a major zoo.

Attachments

Last edited: